Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for the entirety of Final Fantasy XIV, in particular for Shadowbringers up to the patch 5.3 quests.

When I think of heroes in Final Fantasy, I think of the Warrior of Light from the original game. A nameless, stoic figure. A blank slate of a character. This is essentially what your Warrior of Light in Final Fantasy XIV is — a blank slate you can imprint anything you want onto; I couldn’t really do that with classic NES sprites. Yet the MMORPG, especially by the time Shadowbringers rolls around, seems to encourage you to get attached to your character and see parts of yourself in them. But I never wanted to be a hero. And I’d never gotten attached to a player-created character before.

Everyone invests a different amount in their Warrior of Light, from glamouring to roleplaying to just levelling every single job. Regardless, by the time you reach Shadowbringers and the First, one of the Source’s thirteen reflections, you’ve already been through a lot with your Warrior of Light. Catching up through the Heavensward patches to Stormblood, I saw Kisa as an ideal, a beacon for what I wanted to be. She was confident, clever, and bold — but she also knew how not to be impulsive. My freshly Fantasia’d Warrior of Light was exactly the distraction I sought, and Eorzea would become my place of escape because she wasn’t supposed to be like me.

Kisa Havenash was different. My hero of Eorzea, she isn’t actually my first Warrior of Light. I started playing Final Fantasy XIV back in 2016, but I stopped early the following year and didn’t return until 2021. I needed a fresh start. I’d changed a lot over the four years between logins, including becoming increasingly aware of, and being diagnosed with, anxiety. I lived with this “shadow” that leeches away at me and my love of life and often makes me feel worthless, frozen, reluctant, and withdrawn. My experiences from those initial months of playing the game and the baggage of life from that four-year break weighed heavily on me. That didn’t make me a hero, even if I’d seen “heroes” doubt themselves before.

But Shadowbringers wasn’t interested in distractions. In an interview with PCGamesN after patch 5.1’s release, Final Fantasy XIV director Naoki Yoshida called the story of Shadowbringers “more personal.” While he talked about balance and “both elements” (light and darkness), I think Yoshi-P also implied that our perspective is equally important. That’s because the expansion doesn’t just give the Scions the chance to shine; specifically, your Warrior of Light is at the front and centre, more than during any other part of the MMO. The subversions and questions Shadowbringers brings into the fold tease apart your Warrior of Light. It’s all of this that hit me on a personal level, cutting my anxiety free and letting it hang out to dry in the open for all to see.

Just about everything in Shadowbringers is designed to unsettle. There’s an uncanniness to almost everything about Norvrandt. Lavender-coloured grass blankets Lakeland, and lilac-leaved trees adorn it. Kholusia, Ahm Araeng, and the Rak’tika Greatwood are like sombre, washed-out mirror images of La Noscea, Thanalan, and The Black Shroud, respectively. The races are similar to those on Eorzea, with these variants sharing names with Final Fantasy XI races. And the roles of darkness and light have been reversed. At the start of Shadowbringers, you’re all alone in this strange but familiar world. Even characters you meet along the way share names with former allies whom you’ve lost.

Early on, you have to rendezvous with the twins — the youngest members of the Scions, Alphinaud and Alisaie. With Alphinaud, my character sneaks into Eulmore, a city where the wealthy live out their days in grotesque, decadent bliss, exploiting the poor to satisfy their selfish desires. There, they watch a Mystel, Kai-Shirr, cut a piece of flesh from his arm at the request of Eulmore’s leader, Vauthry. Kai-Shirr mutilates himself just to feed the sin eaters, porcelain-looking creatures warped by primordial light. Blood oozes out of his arm as he cries for help and winces in pain. As the man clutches at the gouge, the wound on his forearm and the claret red staining his skin draw my eyes. Alphinaud and the Warrior of Light couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t do anything. I clam up. I’m shaking, and I can barely muster the energy to get through the cutscene. When I eventually do, I walk away from the game to calm down.

Moving on to Ahm Araeng, things don’t get any easier after finding Alisaie fighting sin eaters to protect the sick and the carers at the Inn at Journey’s Head. The inn is where those contaminated by too much light are allowed to live out their final days in peace and pass in as little pain as possible. After an extremely sick boy, Halric, escapes to find a sin eater, a Hume carer named Tesleen chases after him. Seeing the boy in front of a winged, colourless creature, Tesleen runs in and attacks it, but it stabs her before she can get away with Halric. With her dying breath, she puts her hands on the boy’s cheeks and, gasping, says: “We all deserve happiness … wherever we can find it… The time left to you … is precious …. No one should die … in pain ….” Alisaie and my character bring Halric back to the inn, but they couldn’t save Tesleen before she turned into a sin eater and flew away. Kisa couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t do anything again.

I returned to the Crystarium. I was exhausted. Tesleen’s words rang in my ears. But did I deserve happiness when I failed? During these early instances in Shadowbringers, some of my greatest fears had been laid bare in front of me. Failure. Disappointment. Pain. Anger. Suffering. Helplessness. I remember tensely gripping my controller as I ran through Holminster Switch for the first time. As I cut down Tesleen and flames ate the village around us, I was still processing events. How my heart felt heavy as the Crystal Exarch called my Warrior of Light the Warrior of Darkness. That last part struck me. Watching my Warrior of Light’s face, she looked unsure, concerned with that title.

It’s not that these instances were even the first time Kisa or I had seen awful things happen. She’d watched Moenbryda die at the hands of Lahabrea. She’d seen the Ala Mhigans struggle as Zenos cut them down. She stood as Yotsuyu became Tsukuyomi, who had to relive her trauma. It was that in Shadowbringers, they were personal to my Warrior of Light and me, and they showed me my anxiety on the screen. I saw my anxiety in Kisa. This just piled more pressure on me because now I was looking at a reflection of myself in some ways. Yet Kisa was a hero in many people’s eyes.

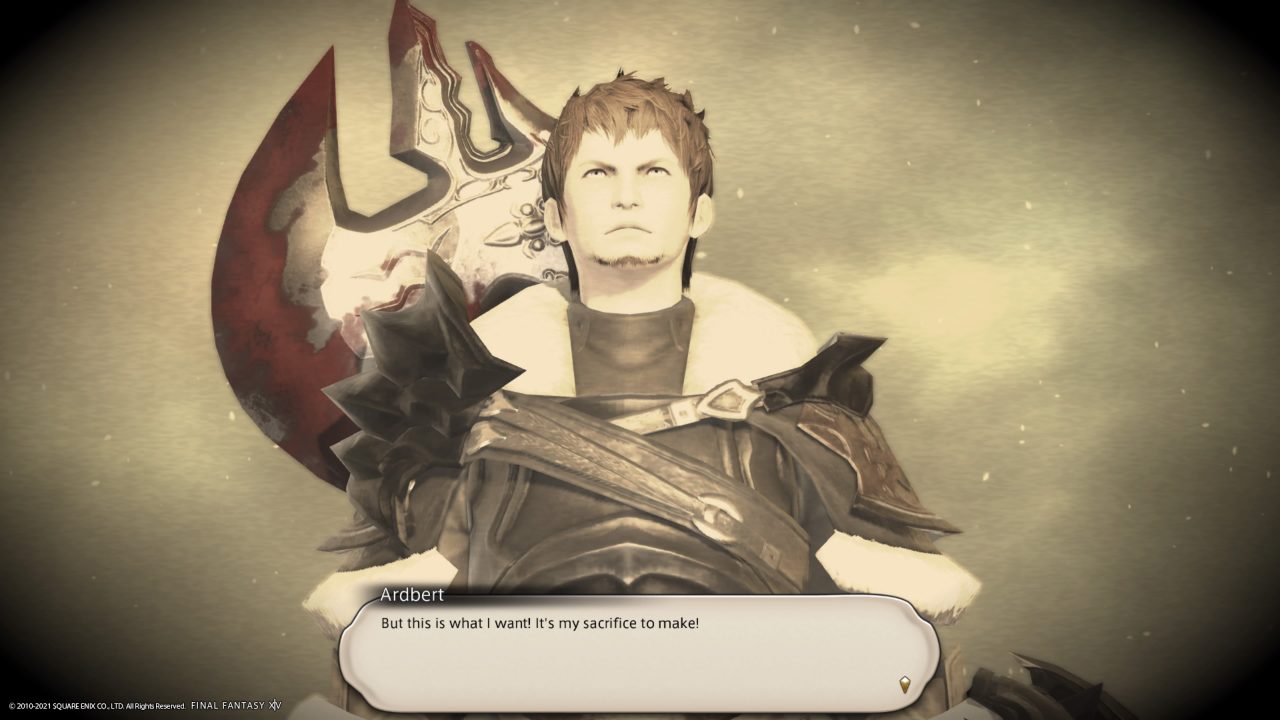

Soon after Holminster Switch, the spectre of Ardbert approaches the Warrior of Light. I was surprised when I saw the former leader of the “Warriors of Darkness” from the Heavensward patches. He clashed with the Scions numerous times to save his home, the First, from the Flood of Light. But I remembered his speech from back in Eorzea. His cracking voice and visible pain had been etched into my mind as he claimed: “… we never aspired to be Warriors of Light. But word of our deeds spread, and soon people were calling us heroes. They placed their hopes and dreams on our shoulders and bid us fight for all that was good and right.”

I understood what Ardbert was saying back then, but it rang truer now. Trapped in another world and desperate to save her own home, Kisa’s emotional state is similar to what Ardbert’s was back then. This responsibility weighs on Ardbert because his wish for the light to prevail over darkness caused the Flood, whose luminescence swallowed up most of the First. The idea that light, instead of darkness, can poison is unsettling. Even with the genre’s obsession with these pure, holy religions being corrupt, it takes a moment to adjust — especially when darkness is suddenly good. It probably felt the same for Ardbert, a hero who thought light would save the world. And then Minfilia used his allies’ souls to halt the Flood but refused to take his. He has to “live” and cannot atone.

Ardbert follows you around throughout Shadowbringers, and as you explore Norvrandt, you find out more about him and his allies. Ardbert sees places, ruins, and people, and he reminisces. As he does this, he’s happy. He’s smiling. I’m smiling, too. This is what he fought for: his friends, these places, and Seto. He carries the regret and failure — that he couldn’t save these things and that he can’t interact with those people anymore. In remembering and talking, he was calming me down. He also reminded me of Haurchefant’s dying words, easing the weight of being a “hero.” Kisa is fighting for Eorzea, after all. Isn’t that enough? That you’re alive and helping others — your existence and support — is often enough.

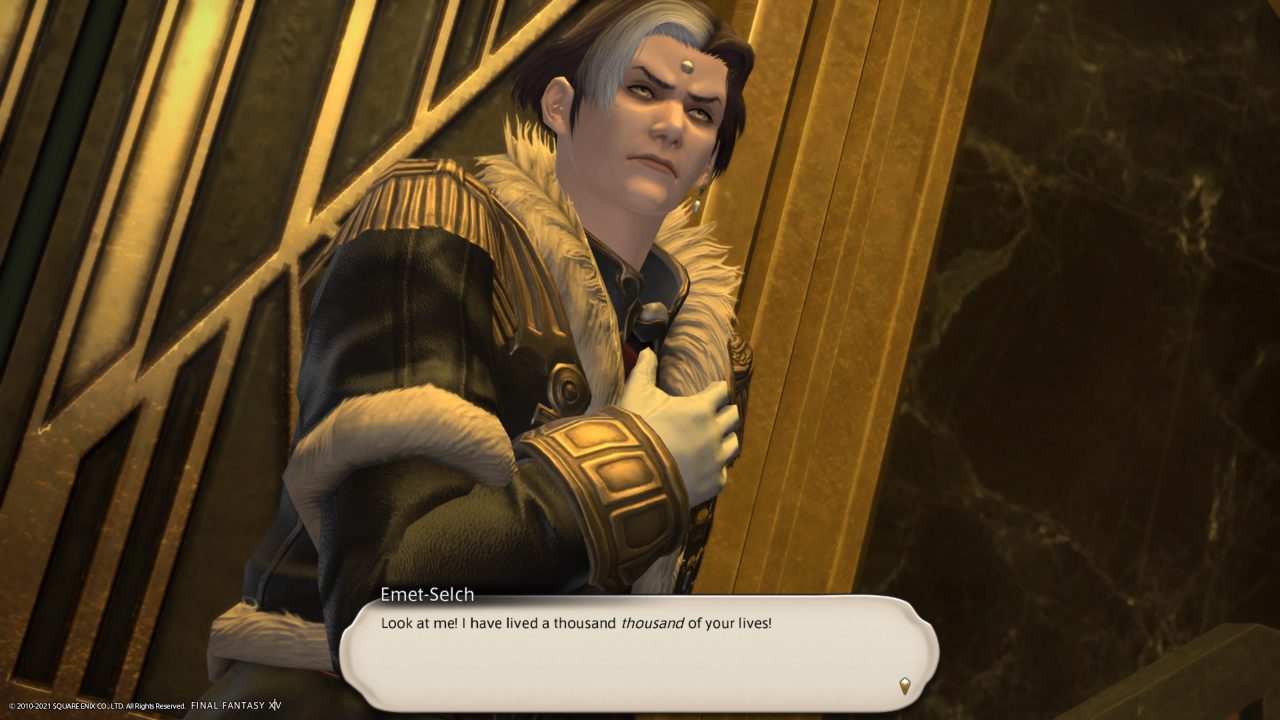

Ardbert isn’t the only “hero” in Shadowbringers. Emet-Selch, while not a hero, also has something worth fighting for. And if we’re going by Ardbert’s example, that means something. The Ascian also follows you and the Scions around Norvrandt, chiming in nonchalantly when he feels the need to. He’s charming, cynical, and solemn all at once, sauntering around while also hunched over. He’s not like the other Ascians we’ve encountered at all, and his presence is another thing that makes me uneasy for the whole of Shadowbringers — even after he saves Y’shtola’s life.

But he invites himself along with your character as a test to see if the Warrior of Light, if Kisa, could cope with the light and return to their former self — Azem. Like the Flood consuming Norvrandt, Emet-Selch uses the light against your character, who has been absorbing the light from the Lightwardens throughout the First, and allows it to start consuming your Warrior of Light. It’s another moment of powerlessness. Especially when the person who has been looking up to you the most — the Crystal Exarch, whom you now recognise to be G’raha Tia from the Crystal Tower storyline in A Realm Reborn — comes to take the light away from you. He fails because Emet-Selch has figured this out. But he’s doing this for you because he admires you. That alone gave me pause and made me feel guilty. Because of me, G’raha Tia gets captured, and his faith in me is misplaced. I felt like a disappointment.

With Ryne able to stilt the light’s consumption, the Scions agree to chase Emet-Selch down and go to The Tempest, an underwater location where the Flood has lulled the stormy seas. It’s here where that knot in my stomach comes back. Despite the Scions’ determination, the sombre, reflective, and eerily calm waters made me feel like I was sinking slowly. Kisa has been lured here to turn into a Lightwarden in a dignified manner, where no one can see her. And, honestly, I wanted to. I’ve wanted to hide away or disappear in situations where I have failed, and The Tempest reminded me of those feelings. But this sedate seabed hides more sorrow beneath the sand — and more images, or illusions, that represent failure.

Emet-Selch has recreated Amaurot, the Ancient city, from his memories. Here, he lies in wait, anguished, reflective, and disappointed in the Warrior of Light. It’s dark and empty, with Amaurotian spectres towering over your characters. It feels like walking through the mind of someone who has experienced failure, longs for something, and is struggling. It also reflects how I feel when I want to bury myself away from my thoughts and anxiety. Amaurot is the city, the home, Emet-Selch failed to protect. And to make the Warrior of Light understand, he makes them relive the calamity that destroyed it. He makes Kisa relive his trauma.

By this point, I understand Emet-Selch’s pain, his desire to bring back the people he loved — and still loves. His “world will have no need for heroes,” he says, as he faces down the Warrior of Light, likely because he has been let down by one “hero” before or because the weight of being a potential “hero” to the Ancients (if he succeeds) is a heavy one. Just like Ardbert. Just like Kisa. But he makes a mistake, seeing all life in the world as inferior, as shards of the Ancients. His disregard for human life, for the lives we have come to love, makes him our enemy. This realisation invigorates me.

Kisa and Ardbert become one, and G’raha, safe from the Ascian’s grasp, summons seven other Warriors of Light to fight alongside me. Seven other real people who play this video game. Seven people who are there to help me, even if I fail a duty in front of them or don’t know what I’m doing. I drew comfort and strength from that, and the eight of us worked together to defeat Hades.

And when we do, Kisa is asked by Emet-Selch to “Remember us. Remember that we once lived.” The words hang in the air, and I can feel the tears stinging my eyes. He asks her to carry the legacy of the Ancients with her, to remember the fallen. We had passed Emet-Selch’s second test to prove that humans now are worthy of protecting the star they live on. But I also saw it as a moment to acknowledge our mistakes. Because, as humans, as heroes, we all make mistakes. The Ancients were not being acknowledged, nor were people willingly accepting the responsibility to protect the star. Now that we have taken on that burden, we must ensure people never forget the first people who tried to do the same. I could not let someone else down. We’d already become one with Ardbert, understanding and redeeming him. And while Emet-Selch’s planned genocide is unjustifiable, I can empathise with the pain.

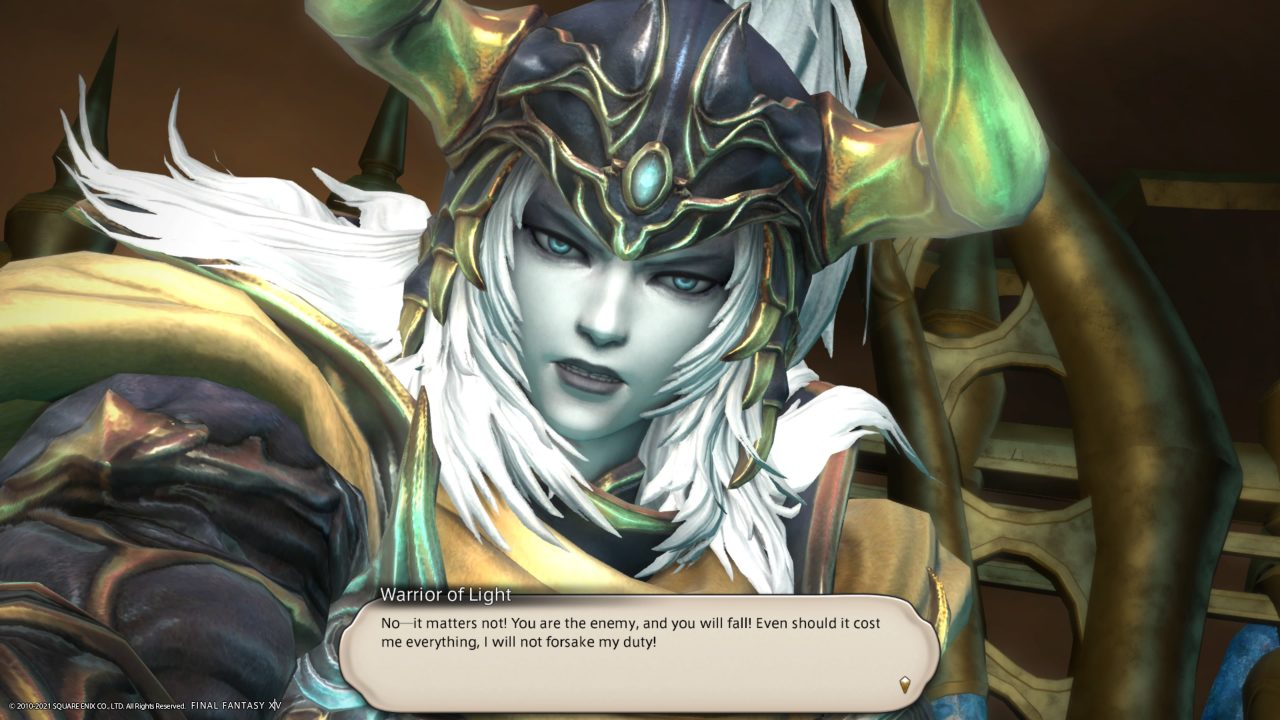

Soon after, Elidibus — another survivor of the calamity who unnervingly often disguises himself as Ardbert — arrives to remind Kisa, and me, where our place is. Just like Emet-Selch was allowing the light to consume your character, so too does Elidibus weaponise that element. In fact, Elidibus is that very classic image of a hero I mentioned at the start — the Warrior of Light. Handsome, stoic, stalwart. It’s a fantastic Final Fantasy reference loaded with connotations because this Warrior of Light isn’t a blank canvas; he is a man that carries thousands of years of pain, regret, guilt, and desperate hope. He’s not the image of the hero I’d imagined as a kid.

I don’t have thousands of years on me, but those feelings — especially desperation — ring true throughout a lot of my life, with regret and guilt eating away at me for small things like forgetting to reply to something or even wanting to talk to someone. But seeing these “villains” struggle so desperately to restore a world they lost, and those they loved, made me realise that this is exactly what your character is doing. Kisa is struggling to return home because if she doesn’t, it’s likely Eorzea will fall. Facing off against Elidibus, she looks determined, this time using Azem’s crystal to summon seven other allies to help her.

In the prior dungeon, The Heroes’ Gauntlet, Elidibus forces you to fight several classic Final Fantasy jobs and figures that refer to other Final Fantasy characters — all heroes. It’s not just a gauntlet for your hero, but a gauntlet of heroes from other worlds. We’re all fighting for something dear to us, something that our loved ones back home wanted. And various factions from across Norvrandt come to help you because you have helped them. Knowing I had friends who could help, and friends I would help whether or not I succeeded, was a relief — especially after Elidibus stood in front of us and called us “death” hours earlier. And in a way, we are. We have killed countless people and creatures in the pursuit of saving the world. And we are about to prevent Elidibus from reaching his goal. But we have a purpose, something to believe in: hope.

That hope, coupled with seeing these “heroes” struggle with very human struggles, is what helped me reconcile with my anxiety. It meant I could stand in front of this Warrior of Light, who suffers, struggles, and clings to some vague hope, promises he does not remember. I could recognise his pain and see it in myself, during times where I could barely believe in myself, like when Kisa looked concerned with her Warrior of Darkness title. After the fight, seeing Elidibus’s true form — a child — made it clear to me that responsibility is a lot, and pain is a lot, but these titles are not something we choose. Nor do we choose our struggles and feelings. But we can learn how to move forward with these titles, these differences, and these feelings, and it’s still okay to have them.

When the Crystal Exarch says, or when Amanda Achen sings, “Stand tall, my friend,” I would sit up straight. Not like I was standing tall, but like I was taking a sharp intake of breath to prepare myself for some kind of responsibility I had no faith in myself to carry. But those words to Kisa and those lyrics to Emet-Selch are meant to ease the burden. Everyone needs help, and everyone needs hope. And even heroes get anxious. Shadowbringers shatters the heroic image, but it’s both a celebration and a deconstruction of role within the Final Fantasy series. There is no one template or mould a hero can fit, and they certainly can’t be perfect (even if G’raha Tia thinks Kisa and everyone else’s Warrior of Light is perfect). We might doubt ourselves sometimes, so intensely in my case that it stops me from doing anything, but as long as we have a purpose for living, for doing what we do, then we deserve to be here.

I knew coming back to Final Fantasy XIV would be difficult and that I would be nervous about catching up, learning, and relearning mechanics. I knew I would have to contend with feeling guilty for dying over and over and feeling like a disappointment to other players. I still struggle now, sometimes. But Shadowbringers made me see through some of the lies my anxiety whispers to me.

So as I look back at my Final Fantasy XIV journey and look ahead to Endwalker, I can say that I have found hope. And with that hope, I will walk to the very end.