It’s no secret that video games can make us happier. Research in the field of clinical psychology has shown that video games trigger a response in the brain’s pleasure center, and there’s debate in the field about whether or not this can lead to an actual addiction. Scientifically speaking, there is a reason for why you get such a rush from clearing a column or row in a puzzle game, and why playing along to your favorite rhythm game can make you feel such intense joy. It’s also been shown that routines and habits can have an extremely positive effect on us. In an interview with The Chicago Tribune, social psychologist Wendy Wood, whose research is focused on the behavioral effects of habits, was quoted as saying that habits, “Help us get through the day with minimal stress and deliberation.”

The RPG genre introduces habits to the player in the combination of a game’s combat system and a gameplay mechanic known as “grinding.” “Grinding” is the term given to the process of having to start, finish, and then repeat repetitive tasks until a certain goal is achieved. In the context of RPGs, this is usually seen in the way a player initiates battle, wins the battle, and then repeats the formula until they reach a desired experience level. It’s not uncommon for RPG fans to say that they enjoy grinding, and for the exact reason Dr. Wood described.

But the psychological impact behind video games gets more interesting. A study published in 2009 showed that the video game Tetris can actually reduce the amount of flashbacks experienced by sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the study, participants were shown a traumatic film of real injuries and deaths, then took a 30 minute break; participants were then selected at random to either do nothing or play 10 minutes of Tetris. Those who did play reported a significant decrease in flashback frequency over the course of a week. So, is Tetris just magical? Well, not exactly.

The study was pushed forward with the theory that, “Cognitive science suggests the brain has selective resources with limited capacity” and, “the neurobiology of memory suggests a six hour window to disrupt memory consolidation.” The study notes that trauma flashbacks are, “Sensory-perceptual and visuospatial mental images,” and because, “visuospatial cognitive tasks selectively compete for resources required to generate mental images, […] a visuospatial computer game (e.g Tetris) will interfere with flashbacks.” It should be emphasized, however, that the finding suggests a game can only do this when performed within the time window for memory consolidation (i.e the process of converting short-term memories into long-term memories).

Basically, because video games are a visuospatial activity, and because participants played one directly after witnessing traumatic events, the brain became distracted when processing the traumatic events and this impacted turning them into memories that could later be recalled.

This psychological recipe is the reason that I took so strongly to video games during my childhood, a time in which I was badly abused, both mentally and physically. Whereas most kids my age took to games for a mindless and enjoyable activity that helped them unwind from school, I took to them for a coping mechanism. Games weren’t an activity for me, but rather, a necessity for my psyche. In fact, when I think about my childhood, I can only really recall bits and pieces—I don’t have very solid memories that I can recall until my preteen years. It’s hard to describe, but imagine that your mind is filled with fog. Sure, you can sometimes make out things through the fog if you concentrate hard enough, but for the most part, it’s just too exhausting to even attempt to see.

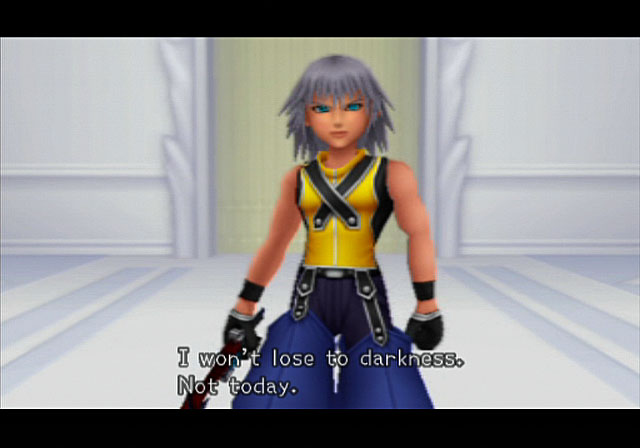

The memories from my childhood that I can recall easily are ones that are focused on video games—specifically, my favorite (and first) RPG, Kingdom Hearts. Though I had played games like Tomb Raider and Super Mario 64, this was the first game to truly make an impact on me. Being a victim of abuse, I didn’t have many friends, both because I wasn’t allowed to have any real social interaction and for the fact that I withdrew from my peers; isolation is a common symptom of PTSD, and only feeling comfortable when alone is something I’m struggling with to this day. For those unfamiliar with the game, its central theme is the raw power of friendship and finding your inner strength through opening your heart. This was a new concept for me, since my instinct, even at seven, was to close myself off from others.

Throughout Sora’s journey, his life became intertwined with countless characters, and he becomes visibly stronger the more he lets people into his heart. There’s a bit towards the end of the game when Sora, now without his signature Keyblade, discusses this with his best friend, who’s now consumed by darkness and has removed others from his life. “Although my heart may be weak,” he says, “it’s not alone. It’s grown with each new experience and it’s found a home with all the friends I’ve made. I’ve become a part of their heart just as they’ve become a part of mine. And if they think of me now and then… if they don’t forget me… then our hearts will be one.” It’s incredibly cheesy, but it was exactly the message that the seven-year-old me needed to hear. I didn’t connect to Sora because he was the complete opposite of me and my beliefs, but I did connect to characters who were consumed by the game’s idea of darkness—characters who rejected the idea of a powerful heart and the bonds of love. I grew up thinking that not letting others in made me stronger, but this was the moment in which the younger me realized that the opposite was true.

What’s magical about a game like Kingdom Hearts is that while there is a definitive psychological reasoning as to why the gameplay impacted the process of me consolidating the events of my abuse, it also managed to weave a narrative that spoke to me while doing so. This combination of psychologically-pleasing gameplay and ability to invoke emotion through story is the power of video games as a narrative medium, and I feel that those who question whether or not video games as a whole can impact us the way literature or cinema can haven’t grasped this. Perhaps more than any other medium, video games can help us forget the pain in our current lives while exploring themes that have the potential to leave a lasting impression on us.